Click here to get this article in PDF

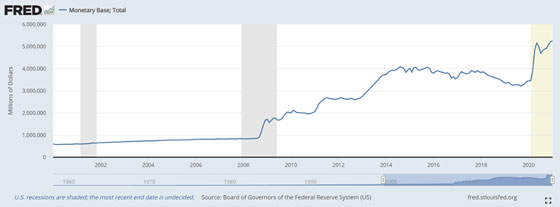

By the M0 measure of the money supply, there was a 52% increase between February 2020 and January of this year. This is a graph of M0 going back to 2000.

There. Proof of the coming hyperinflation. It took centuries to get to $3.4 trillion monetary base, and less than a year to increase it by over half. QED. This is all you need to know!

At least, so say those who are certain that prices are set to skyrocket. And who, of course, also say you should buy gold as it will skyrocket too.

On the other side, the hacks and apologists for the central bank and deficit spending argue there’s nothing wrong with the current monetary and fiscal policies. Paul Krugman, in this debate, asserts (in between many weasel words) that the Biden $1.9 trillion spending package won’t cause much inflation.

A Bank of America survey seems to confirm this, finding that 64% of people planned to pay off debt, save, or invest their $1,400 checks. The rich are not going to receive anything, so this response is showing the middle class is not planning on living large with this largesse.

One ugly fact is that the price of oil has shot up to $65. And the twin to inflation is rising interest rates. The 10-year Treasury yield has spiked up to 1.6%. Do these data points not argue for accelerating inflation?

At the same time, most car commercials advertise 0% interest for 5- or 6-year loans. This is not only a data point for lower interest rates—what would the Treasury have to be, for consumer credit to be zero interest?—but also for soft prices. The price of the car may not be discounted that much, but zero interest is a subsidy worth an additional thousands of dollars per car.

A Glaring Fallacy

Krugman argues that giving unemployed people free money is not stimulative. By the implication of his economic theory, this means non-inflationary. His reason is that it is simply replacing the income that people would have gotten, if they had been employed. And therefore, it is not giving them additional purchasing power.

The fallacy in this is so glaring, that we expect a precocious eight-grader could see through it. When those people were working, they were producing goods and services. Now they are paid the same, but producing nothing. That is, welfare checks prop up demand but lockdown cuts down supply. If supply falls but demand remains the same, we would expect higher prices.

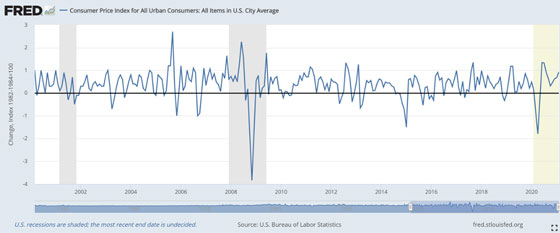

We see it in certain goods. The Consumer Price Index has perked up these last few months. But look at this chart, going back to March 2020, showing year-on-year change in the CPI.

This data is through last month. The inflation number has not gotten out of range, despite the breathtaking increase in the monetary base. Any argument for extreme inflation will have to say, in essence, “yes, but it’s coming”.

Is it? Before we get to that, we encourage the reader to think about all the previous times that the commentariat got excited during this long period of falling interest rates, telling us that a big inflation is coming.

Another thing we often hear, especially in the alternative investments community, is that the official CPI measurement is a lie. It’s not a lie. It’s something else.

Some debate what goods ought to be in the basket measured by CPI. And what product ought to replace one that becomes obsolete, such as buggy whips. These quibbles are the inevitable result of the fundamental confusion built-in to the nature of the index. The CPI violates a law of arithmetic that we all learned in fourth grade.

You cannot add apples to oranges.

The CPI does not only add them, it averages them. An average of two numbers is (A + B) / 2. So, of course there will never be agreement on which goods are included, or the proper weighting. And therefore, on what the right number for inflation is.

But one thing should be clear. You could not obscure a massive drop in the value of a dollar, just by switching one consumer good for another in the CPI basket of goods.

Prices & Interest Rates

We have often written about the fact that prices move with interest rates. The relationship is not merely correlation. It’s causal (Keith will be presenting his radical theory of interest and prices at the Mises Institute Austrian Economics Research Conference this week, in Auburn, AL).

When interest rates fall, it lowers the cost of borrowing. At any given moment, there are many businesses that are considering borrowing to expand. Or borrowing to buy equipment to replace labor. But at the current rate of interest, it doesn’t work. What happens when the interest rate drops?

Their business case then becomes sound. So they borrow to increase production. This puts downward pressure on prices. Think of what happens if the supply of hamburgers increases, while demand remains the same. The price of a hamburger drops.

Falling interest has been the trend since 1981. But prior to that, we had rising rates. During that period of rising rates, producers who planned to borrow money to replace worn out capital equipment found that it didn’t work at the new, higher rate. However, what did work well indeed was to borrow to buy raw materials. And to borrow to finance work-in-progress, a buffer of partially completed goods in between each step of the manufacturing process.

In a period of rising rates and prices, the longer it takes between when a company buys the ingredients until it sells the finished goods, the more profit it makes. Thus they have incentive to borrow more to carry more materials in their warehouses.

This definitely does not describe the present environment.

Today, the monetary forces are pushing prices down. However, there are three nonmonetary forces that push prices up: regulatory, fiscal, and social.

Prices & Useless Ingredients

We have written many articles about mandated useless ingredients. This is when the government forces gasoline companies to add ethanol or MBTE. These additives push up the cost of petrol (we have read numbers around 25 cents per gallon). Gas is a low-margin commodity, and an increase in the cost per unit causes an increase in the price to the consumer.

Useless ingredients are being mandated all across the economy: supply-chain tracking, bathrooms compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, calorie labels on every item on restaurant menus, minimum wage and other labor laws such as the forced hiring of extra workers, umpteen airbags in automobiles, etc.

Some of these things may be good, and might have been chosen by free actors in a free market (though not in the rigid, unthinking, and expensive ways forced by regulators). However, the point remains. These are costs that do nothing for consumers. Most people don’t even know about them. They just say, “wow, the price of gas went up.”

Prices & Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy works similarly. It adds cost, and hence pushes up prices, but few people are aware of it. Speaking of gasoline, we observed a gas tax hike in California a while back. We thought that, once people forgot about the tax hike, they would just think of the rising price of gas as part of inflation.

No discussion of forces that push up prices would be complete without discussing a deliberate reduction in supply based on social concerns. We refer to the government response to Covid. Looking just at the meat industry, forced plant closures reduced supply of meat last year. Since demand for food is quite inelastic, the price had to rise dramatically in order to force the marginal consumer to eat less meat.

We realize that the mainstream includes all causes of rising prices in their definition of inflation. However, regardless of the words used, we differentiate these nonmonetary forces pushing up prices as opposed to the monetary forces pushing them down. This distinction is important, especially if we want to predict what comes next.

This is because a monetary force not only cause prices to move, but the resultant price move transmits feedback to that monetary force. It’s a positive feedback loop. It tends to keep running in the same direction for a long time.

By contrast, nonmonetary forces are one-time events, that cause one-time price adjustments. A 25-cent gas tax causes a 25-cent (or 23- or 26-cent) price hike. But there is no further motion after that, unless the legislature meets again.

“Yes,” some will say, “but interest rates have been rising.”